About an hour north of Naha Airport is Ryukyu Mura (Ryukyu Village). It is a showcase of life in the days of the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429-1879), when the independent country was a tribute state of China before coming under the sway of the Satsuma domain.

As well as buildings in traditional style, there are examples of the crafts and customs. This includes a charming dance show of elegant movements to the Polynesian sounds of Okinawan music.

In one of the compounds is a display of Ryukyu religion. This is of particular interest because of the light it sheds on the southern strand of overseas influences that were moulded into what we now know as Shinto. As Fabio Rambelli writes in The Sea and the Sacred in Japan: “Many folklorists, beginning with Yamagita Kunio and Origuchi Shinobu, have taken Okinawan religion as a remnant of ancient Japanese religion and, often, as the model for Japanese religion as a whole.”

At the entrance to the compound is a board which states as follows:

Utaki is the symbolic place in a village which is the sacred place to pray to ancestral monument or guardian of the village. Every village has one. Rocks and trees are at the centre before which incense is placed.

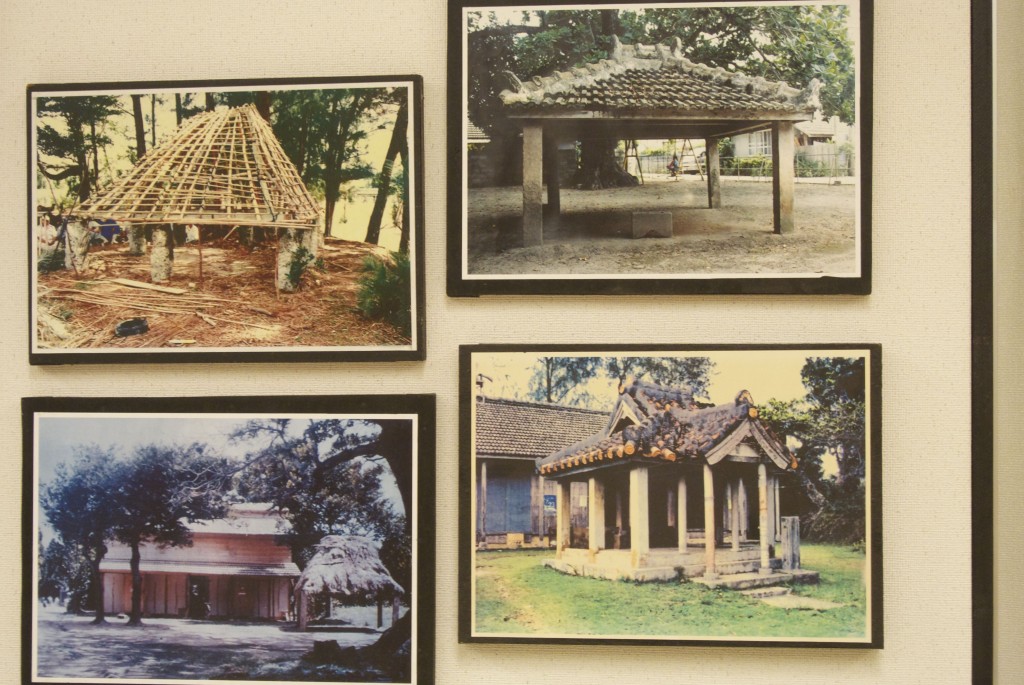

The holy tree is called Kuba (or Shuro palm tree). Ibi is the place where gods come down and only female shamans can enter. Rituals in the shrine are called Kami Asagi Tun located close to Ibi. Kami Ashagi Tun is built low to prevent animals entering.

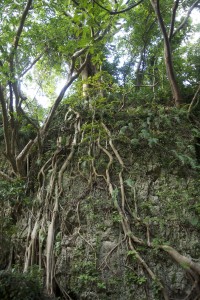

Banyan trees come from India and south-east Asia. Here the roots of a big mother tree are connected with a child tree. The board continues: “It is believed that a Kijimuna (fairy) lives in old banyan tree. Banyan trees are used for lacquer ware and manure, and the tree bark are used for remedy. The parent tree is over 180 years old.”

To one side is a small section devoted to religious festivals. A notice board states that ‘Most festivals in Okinawa are dedicated to god of nature and ancestors for harvest and health. HA-RI (Festival for ocean god, Niraikanai) in every fishing port.’ (sic)

*******************

For other pieces on Okinawan religion, see here on the Dragon King and the first of five articles on Okinawa. Or click here for a piece on Miyakojima. Or here on Amami Oshima.

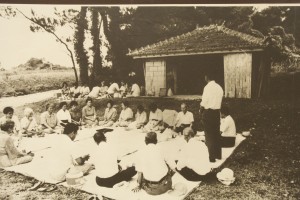

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.