My next visit was to Hakuto Shrine, notable for enshrining a white rabbit. Not Alice’s white rabbit, of course. In fact, not a rabbit at all but a hare, as the Japanese language makes no distinction between the two. The Hare of Inaba is its name, and it appears in Japan’s oldest book, the Kojiki (712).

‘Do you know the story?’ my guide asked.

‘More or less,’ I said. ‘There was a hare living on Oki Islands which came to the mainland where it was skinned and tortured by some bullies, but rescued by a younger man, who is now known as the kami, Okuninushi.’

’Oh, you know very well,’ she said. Although the story is well-known, she had made a point of learning the details to explain to her customers. ‘The hare wanted to get to the mainland,’ she continued, ‘so it challenged some sharks to see which animal had more followers.’

‘On the Oki Islands, right?’

‘Yes. The cunning hare persuaded the shark leader to line up its followers all the way to the mainland so that they could be counted, then used them as stepping stones to hop its way across the sea.’

The rest of the story reads like a moral tale of animal rigts. When the sharks realised they had been duped, they seized the hare and tore off its fur in revenge. Then along came the sons of the Izumo king on their way to court a princess, and when they came across the poor hare pleading for help, they told it to wash in the sea and let the breeze dry it off, knowing full well the salty water and wind would bring more pain. However, the youngest called Onamuchi (aka Okuninushi) took pity on the hare and after the others left told it to use fresh water and wrap itself in healing medicinal leaves. Like all good folk tales, there was a reward for the hero when the hare revealed itself as a deity and granted to Onamuchi the right to marry the princess.

Hakuto Shrine is sited next to the beach where the hare supposedly arrived onto the mainland. A small step for the hare, a big step for mythology. The nearby Mitarashi Pond is where it supposedly purified itself., and one way of decoding the story is to see it as marking the arrival of a ‘heavenly’ (I.e. undefiled) migrant clan from Korea.

Since animals sense the unseen better than humans, they are usually regarded in Shinto as mediators between this world and the other. Here, however, the hare is the main kami of the shrine. The colouring may have played a part in this, for Inaba hares turn white in winter, and white is a signifier of purity. It is an attribute widely shared amongst the religion’s sacred animals – white foxes, white snakes, white horses, white deer, white doves.

Purity underwrites the story in another way, as washing in fresh water suggests misogi, a Shinto practice involving ritual immersion in cold water. The purpose is to refresh and renew the human spirit, ‘polluted’ through being in a material world. The striving for purity has left a mark on modern-day Japan with its emphasis on cleanliness, reflected in the tendency for white cars, in politicians who wear white gloves, and in the readiness to wear white masks.

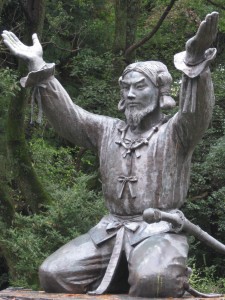

Next to the steps leading to the Worship Hall is a statue of a youthful looking Onamuchi together with the hare, and at the shrine office white stones are on sale for tossing onto the lintel of the torii for good luck. I watched my taxi driver throw a coin into the offertory box, ring the bell and do the standard two bows, two claps and one final bow. Afterwards I asked if she had prayed, and she told me she was making a wish for the health of her family. I wondered to what she had made the wish – kami, the white hare, God, Onamuchi? All of them, she said, everything in fact. The universe in general. Wonderful, I thought. The nameless mystery that has neither shape nor substance.