View of Kyoto from the Ryozen area on the city’s Eastern Hills

The Ryozen Gokoku Shrine is not a name that springs to mind when thinking of Kyoto, yet it draws a continual stream of visitors. The reason is that it houses the grave of Sakamoto Ryoma, one of the great heroes of Japanese history. Indeed, some accounts consider him the architect of the Meiji Restoration which turned Japan into a modern Western-oriented country.

Ryoma Sakamoto and friend Nakaoka Shintaro

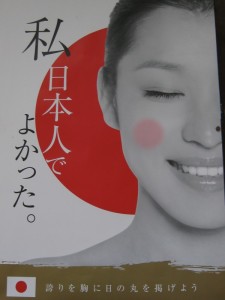

Another important aspect of Ryozen is that it was the origin of Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, as can be read in the account below. Like other Gokoku Shrines, there is a strongly patriotic atmosphere and I was bemused on my first visit to the graveyard to hear a recording being broadcast in English which turned out to be the voice of Judge Pal, who was the only dissenting voice at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal (he claimed all defendants were not guilty).

The article below comes from the Yomiuri newspaper, a noted rightwing publication. It explains the lack of mention of any controversy about the nationalistic nature of the shrine’s museum. It also explains the curious usage of ‘patriot’ in the article. The term is used to refer to those who fought on the imperial side in the war of liberation against the shogunate.

Why should only those who fought on the emperor’s side be considered patriots? It’s a subtle ideological ploy by the writer and a reminder that, as the saying goes, history is written by the victors.

*********************

Finding Ryoma in the Hereafter

Japan News September 17, 2015 By Yasuhiko Mori / Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer

An endless line of people visit the grave of legendary samurai Sakamoto Ryoma, commonly called Ryoma, in the Ryozen area in Higashiyama Ward, Kyoto. Next to his grave is the grave of a close associate, Nakaoka Shintaro. There are also graves of other patriots from the closing days of the Edo period (1603-1867), including Kido Takayoshi, Umeda Unpin, Maki Izumi, Hirano Kuniomi, Hashimoto Sanai and Rai Mikisaburo. Why were so many patriots buried there?

Shinto funeral rites

The Ryozen area was originally part of Jishu Shoboji temple. Murakami Kuniyasu, who served in the Imperial court, purchased part of the premises in 1809 to use it for Shinto funeral rites and established Reimei Shrine.

The grave of Sakamoto Ryoma at the Ryozen Shrine in Kyoto

Under the religious policy of the Tokugawa shogunate during the Edo period, everyone became a parishioner of a Buddhist temple, in principle, and funerals and memorial services were conducted by temples. Shinto priests were not excluded from this rule.

“Kuniyasu apparently opposed the rule,” said Shigeki Murakami, the eighth Shinto priest of Reimei Shrine, where Kuniyasu served as the first Shinto priest. According to Murakami, based on the idea that Japan is the country of the Emperor, Kuniyasu rejected Buddhism, considering it to be a foreign religion, and only carried out Shinto-style funerals.

Retainers of Choshu domain

During the final days of the Tokugawa shogunate, the Choshu domain — where the “sonno-joi” doctrine, which wanted to restore the Emperor while expelling “foreign barbarians,” was popular — buried its retainers who died in Kyoto at the cemetery at Reimei Shrine. The domain’s first burial at the shrine took place in 1862 when Matsuura Shodo, who was taught under Yoshida Shoin at the Shokasonjuku academy, was buried.

Following this, many supporters of the sonno-joi movement from the Choshu and other domains were buried there. That same year, the shrine conducted a rite for the souls of the supporters of the movement who died during and after the Ansei no taigoku purge, or the suppression by the shogunate of those who did not support its policies in the late 1850s.

There is a record showing that Kusaka Genzui, who was a key figure among supporters of the sonno-joi movement in the Choshu domain and is known to have met Ryoma, asked the shrine to perform memorial services for his ancestors for the rest of time.

“Dream” – the inspirational Ryoma Sakamoto ema at the shrine

Reimei Shrine was regarded as a holy place among supporters of the sonno-joi movement, according to Kiyoshi Takano, a novelist who is familiar with the history of Kyoto during the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate.

On Nov. 15, 1867, of the lunar calendar, Ryoma and Nakaoka were assassinated at the Omiya shop and inn in the Kawaramachi district of Kyoto, and their bodies were transported to Reimei Shrine in the evening of the 17th by their associates, including Kaientai, a corporation established by Ryoma. There is a record showing that the shrine conducted a Shinto funeral rite for them before burying them. In some cases, shrines enshrine only the souls of the dead, but Ryoma and others were actually buried at the site.

Managed by Shokonsha shrine

The Meiji government, launched following the Imperial restoration, established Shokonsha shrine at the Reimei Shrine’s cemetery in 1868 to enshrine the souls of people who died because of the chaotic state of affairs after the arrival of U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853, as well as of the war dead in and after the Battle of Toba-Fushimi in 1868.

In 1877, the government confiscated most of the Reimei Shrine’s cemetery and precinct, and had the government-owned Shokonsha shrine manage them. Shokonsha shrine was later renamed to what it is currently known as, Kyoto Ryozen Gokoku Shrine.

“I want to be the present-day Sakamoto Ryoma,” runs a heartfelt tribute at his grave

During that time, Tokyo Shokonsha shrine was established in the Kudan district of Tokyo, and the enshrined “divine spirits” in the Shokonsha shrine and the Reimei Shrine in Kyoto were moved to the Tokyo shrine. Tokyo Shokonsha shrine was later renamed Yasukuni Shrine.

This means it is possible to revere Ryoma at Yasukuni Shrine, but if you really want to show your esteem for the legendary samurai, visit Ryozen, where his remains are buried.

Influence of Emperor Kokaku

Murakami Kuniyasu, who established Reimei Shrine, served the Imperial court ruled by Emperor Kokaku, whose reign was from 1779 to 1817.

Emperor Kokaku was a descendant of the Kanin-no-miya branch of the Imperial family, but he revived a range of rituals of the Imperial court, which were lost in the medieval period, in an attempt to restore the authority of the Imperial court. Such efforts had an impact on the sonno-joi movement later.

The origin of the Gakushuin schools lies with Emperor Kokaku. The emperor planned to establish an educational institution for sons of kuge aristocratic class families, similar to the daigakuryo (university) in the Heian period (late eighth century to early 12th century). While the plan was not realized during his reign, it was decided that such an institution would be established in 1842 when Emperor Ninko, Kokaku’s successor, was on the throne. The institution was the Gakushuin school, and it was located south of Kyoto Imperial Palace until the first year of the Meiji era. The Gakushuin school in Tokyo was established in 1877.

Worshippers at Ryoma’s grave, before which handwritten tributes are placed. Unusually he was not only given a Shinto funeral but his body was buried in the shrine’s cemetery.

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?