One of the leading arbiters of poetry in early times was Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241), a giant of  Japanese verse who also compiled Hyakunin Isshu – 100 Poems by !00 Poets. Like others of his time, he saw divine purpose in poetry and was careful to distinguish between Buddhist and Shinto verse.

Japanese verse who also compiled Hyakunin Isshu – 100 Poems by !00 Poets. Like others of his time, he saw divine purpose in poetry and was careful to distinguish between Buddhist and Shinto verse.

For Teika and his contemporaries, Japanese poetry had its origins in the Age of the Gods, with the first waka (Japanese poem) being composed by Susanoo no Mikoto. Thereafter it was held that poetry had the power to move the kami and it was closely tied to matters of ritual, proper conduct and even affairs of state. The divine power of words became codified in something called kotodana (word spirit). It’s no coincidence that the ancient word for government was matsurigoto, synonymous with religious ritual.

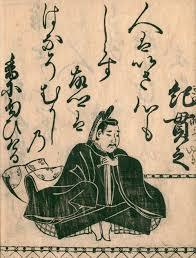

In Robert Huey’s The Making of Shinkokinshu (2002), the author shows that the Poetry Ministry in Heian times, known as Wakadokoro, divided poems into Buddhist and Shinto despite the syncretism of the age. The latter were given a greater sense of awe than their Buddhist equivalent, because the Japanese kami held power over life and death. This is illustrated in an anecdote about Ki no Tsurayuki, whose inspirational preface about the divine nature of poetry is discussed in an earlier Green Shinto posting here.

Once when riding through Izumi province, Tsurayuki passed by the shrine of the god Aridoshi. As it was dark he did not notice the shrine, and while passing by suddenly his horse dropped dead. Only then did he notice a torii and enquired as to which kami lived there. “Aridoshi Myojin” he was told, “who is easily offended. Perhaps you rode past mounted on your horse?”

Tsurayuki was at a loss and summoned the shrine attendant to ask for advice. However, the attendant appeared to speak with the voice of the kami. ‘Since you did not realise there was a shrine, I should forgive you. But you are highly skilled in the way of poetry, so if you can display those skills as you pass in front of me I shall revive your horse. Thus speaks the god Aridoshi Myojin.’

Tsurayuki was at a loss and summoned the shrine attendant to ask for advice. However, the attendant appeared to speak with the voice of the kami. ‘Since you did not realise there was a shrine, I should forgive you. But you are highly skilled in the way of poetry, so if you can display those skills as you pass in front of me I shall revive your horse. Thus speaks the god Aridoshi Myojin.’

Tsurayuki immediately purified himself with water, composed a poem, wrote it on a slip of paper and attached it to a pillar of the shrine. He then began to pray, at which his horse revived and the attendant told him he had been forgiven. Here is the poem he wrote:

Since it was midnight. Amagumo no

With heavy rain clouds tatikasanareru

Layered thick, yofa nareba

How was I to know as I passed kami Aritohoshi

That the kami Aridoshi was there? omofubeki kafa

In this way it can be seen that poetry in the Shinto tradition could well be a matter of life and death. Pleasing the kami would bring well-being; violating the Way of Poetry could spell death or disaster. Retired Emperor Hanazono, for instance, who became a Zen monk, wrote in the fourteenth century of a poet who had strayed from the ancient path of poetry and therefore died an unfortunate early death.

Not long afterwards Zeami Motokyo, founder of Noh, wrote that ‘All living creatures and even non-sentient beings have poetry residing within them. The sound of trees, the moving grass, the earth and sand, wind, and ever-flowing water – all of these things embody the soul of poetry. In the spring, a wind from the east makes the forest sing. The wind from the north in the fall blends with the call of insects. All of these sounds are poems in and of themselves.’ (from Takasago)

Exactly!

*********************

For more Shinto poems from the Heian period, please see here.

To convey their delicate feelings the aristocrats used verse as a means of expression, in particular the short poetry form known as waka. This was based on a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable pattern (haiku was formed later by dropping the last two lines). Topics ranged from nature appreciation through the whole gamut of love found and lost.

To convey their delicate feelings the aristocrats used verse as a means of expression, in particular the short poetry form known as waka. This was based on a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable pattern (haiku was formed later by dropping the last two lines). Topics ranged from nature appreciation through the whole gamut of love found and lost. Since humans resonate in tune with harmony, runs his thesis, the poet can promote unity by capturing the ‘good vibrations’ in words. These were communicated to others through sound, for waka were not simply written words but meant to be chanted out loud. (Translated literally, waka means ‘Japanese song’ and the verse are referred to as uta, or songs.) You could say then that the poems are a form of harmony in more ways than one.

Since humans resonate in tune with harmony, runs his thesis, the poet can promote unity by capturing the ‘good vibrations’ in words. These were communicated to others through sound, for waka were not simply written words but meant to be chanted out loud. (Translated literally, waka means ‘Japanese song’ and the verse are referred to as uta, or songs.) You could say then that the poems are a form of harmony in more ways than one.