Biodiversity and Spiritual Well-being

Biodiversity and Spiritual Well-beingBiodiversity and Health in the Face of Climate Change, 2019

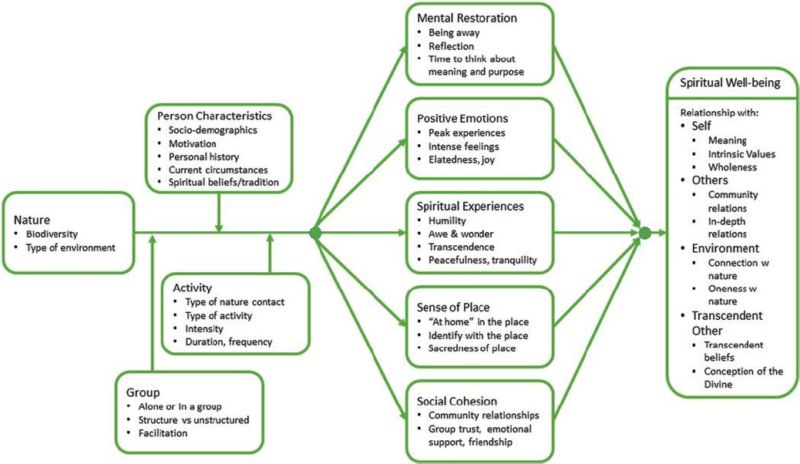

Ethical prescriptions and community practices that can promote ecological conservation are also present in various ‘world religions’ and alternative spiritualities. Whether the divine is seen as transcendent or immanent, dualistic or monistic, the range of beliefs and practices described in this section demonstrate increasing concern for biodiversity and engagement in specific actions to preserve it.The Religions of the World and Ecology series from Harvard University Press illustrates the vitality of concern for ecological conservation within many ‘world religions’. The series includes volumes on Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Daoism, Hinduism, Indigenous Traditions, Islam, Jainism and Judaism. Similarly, various ‘world religions’ alongside other spiritual orientations are included in several scholarly handbooks on religion and ecology (e.g. Jenkins et al. 2017), at least one of which includes a chapter on biodiversity. In Hinduism, for example, natural objects such as rivers, trees, stones and animals can manifest the sacred as forms of divinity worthy of devotion and conservation. As one Hindu woman explains: “When I look into the face of the goddess on the tree, I feel a strong connection with this tree”.Such an orientation can lead to environmental activism, for example, cleaning up the polluted Yamuna River in northern India or protecting sacred groves threatened with deforestation. Similarly, Buddhist environmentalists rely on Buddhist teachings about interdependence to support claims to oneness with nature and conservation. Joanna Macy, an eco-Buddhist activist, writes that in Buddhism the egotistical self is “replaced by wider constructs of identity and self-interest– by what you might call the ecological self or the eco-self, co-extensive with other beings and the life on our planet”. These religious perspectives, based on modern interpretations of ancient traditions, can spur people toward conservation of biodiversity. Indeed, a large-scale ‘religious environmentalism’ movement in America has challenged prior emphases on humanity’s dominion over the earth, instead insisting on ‘creation care’ or ‘stewardship’ as a central religious principle…

New Age and Neopagan spiritualities, including Wicca and Goddess worship, are also engaged in biodiversity conservation, in part because practitioners experience spiritual well-being through interaction with nature. These new religions draw on indigenous traditions, Asian religions and/or Western sources to create holistic spiritualities based on unity with nature and harmony with natural cycles. As Neopagan leader Starhawk writes: “The craft is earth religion, and our basic orien-tation is to the earth, to life, to nature…. All that lives (and all that is, lives), all that serves life, is Goddess” . Identification with nature in all its diverse manifestations impels Neopagans to protect nature through social engagement and religious practice. One survey study showed that members of such alternative spirituality movements view both experiences in nature and environmental actions as spiritual. One practitioner of this Gaia-centered spirituality said that “getting back to the earth” means to “give back and give thanks to the earth, and be more of that one community… [of] oneness”. Based on these views and experiences with nature, many Neopagan and New Age people engage in ecological activism and preservation efforts, including “recycling, tree-planting, alternative energy strategies, petitions, and so forth”.

************

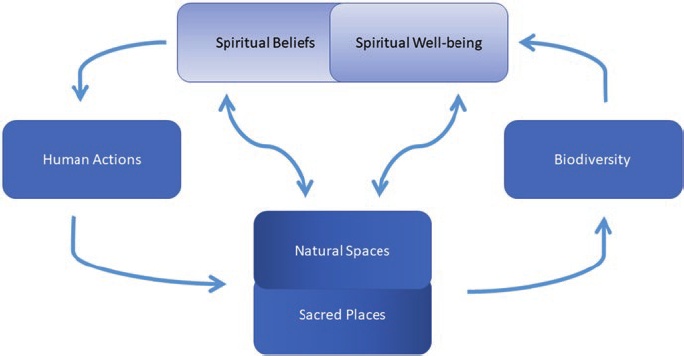

In addition to spiritual beliefs and practices that can foster respect and action for biodiversity, we found ample sources on sacred natural sites as repositories of biodiversity. Spiritual values and taboos associated with sacred natural sites can help to preserve biodiversity In this context, sacred places are natural areas that have special significance for local communities, often linked to religious myths or rites…. Additionally, conservation of these sites aids the preservation of local cultures and their traditional ecological knowledges.Of particular interest amongst researchers in this area are sacred groves and sacred forests.

Sacred forest at Togakushi Jinja in Nagano

Sacred groves are patches of natural vegetation dedicated to local deities and protected by religious tenets and cultural traditions; they may also be tree-stands raised in honor of heroes and warriors and maintained by the local community. Taboos against over-harvesting, harming particular sacred species or disrupting the ecological balance of sacred groves and forests can preserve species richness. For example, the Nkodurom and Pinkwae sacred groves in Ghana have been protected through traditional beliefs and taboos, resulting in preservation of threatened mollusk, turtle, monkey and heron species.

In India, the number and spatial distribution of sacred groves creates a network that preserves “a sizable portion of the local biodiversity in areas where it would not be feasible to maintain large tracts of protected forests”. Local traditions that include worshipping trees in a sacred grove helped to preserve a rare bat species, and, in another area, spiritual beliefs about a hidden shrine within a sacred grove preserved riparian forests and streams.

In central Italy, local Catholic practices around pilgrimage sites have helped to conserve biodiversity through preserving relic habitats and vegetation assemblages, protecting old growth forests and tree species, and maintaining greater habitat heterogeneity due to sacred grottos and water sources. Reflecting on forest preservation by the official association of Shinto shrines in Japan, Rots (2015) observes: “The significance of these forests … extends well beyond ecology and nature conservation proper. Constituting continuity between the present and the ancestral past, they have come to be seen as local community centers that provide social cohesion and spiritual well-being” (p. 209).

Many studies of biodiversity at sacred sites have used standard ecological survey techniques of tree species diversity, tree species richness, regeneration status, floristic surveys of vegetation composition and ethnobotanical uses of species. An alternative approach was taken by Anderson et al. in documenting the biodiversity of sacred mountains in the Himalayas of Tibet. Existing vegetation maps and geo-graphic information systems (GIS) were used to remotely assess species composition, diversity and frequency of useful and endemic plant species. Sacred mountains had significantly greater overall species diversity than surrounding areas. These studies highlight the various measures being used to document biodiversity preservation in sacred protected areas.

A bridge transporting the visitor into a sacred world of nature and renewal