The Shaman’s Rock at Lake Baikal has a cave in which a monster was said to live. It’s one of the oldest shaman sites in the world.

The awesomeness of rocks

Green Shinto has written several times of the spiritual significance of rocks in Shinto (see the righthand column for previous postings). It’s a much overlooked subject. Why? Partly because it is associated with the kind of primitive superstition that Meiji era Japan sought to put behind it. But also partly, I suspect, because rock worship leads back to Korean shamanism and shows that far from being unique, Shinto is inextricably linked with continental nature worship. Just how this conflicts with the insularity of mainstream Japan will become evident in the remarks below.

It was with some delight that I recently came across a video entitled “Okayama: the profound spirit of the rocks” (28 mins). 70% of Japan is covered in mountains and forests, so it’s not surprising that ancient Japanese felt some kind of kinship with them. They even named tribes after the protective mountain beneath which they settled.

‘Since ancient times,’ runs the commentary, ‘people in Japan have felt a deep sense of awe towards particularly impressive rocks.’ It’s not limited to Japan, of course. The same could be said for ancient cultures around the world – you only have to think of Stonehenge, the pyramids and Machu Picchu for example.

Rock power

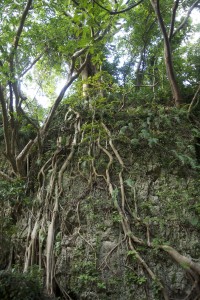

The commentary goes to feature a cave and group of rocks in Okayama, where according to local folklore a demon is said to live – reminiscent for me of the ‘demon’ said to have lived in the Shaman’s Rock on Olkhon Island in Lake Baikal. Rocks as an abode of spirits was part of the Ural-Altaic culture that spread down into the Korean peninsula. In Japan’s syncretic tradition, it is a Buddhist temple rather than Shinto shrine that guards the area, though in times gone by there would have been no such artificial division.

Rocks can provide boundaries and guidelines

‘In Japan we believe that massive rocks such as these are occupied by divine spirits,’ says the guide, typically emphasising the singularity of Japan rather than its continental heritage. It is in such beliefs, deliberately furthered by Japan’s education system, that the roots of Shinto nationalism lie.

‘In the face of this massive power of nature, we can only put our hands together in awe,’ continues the guide, perfectly expressing the animistic roots of the religious impulse in cultures throughout the world. The belief that Japanese are somehow unique in this stems from a binary opposition of ‘we Japanese’ versus ‘Christian Westerners’, so deeply ingrained in Japanese education. Is it too much to hope that one day school textbooks will talk of ‘we East Asians’ and of Shinto as part of ‘shamanistic cultures worldwide’.

Rock of ages

Kitagi Island in the Inland Sea is famous for its granite rock (which was used for building Osaka Castle). One of the quarrymen there says, ‘My father would always tell me the rock is alive,’ and the discussion goes to suggest that newly cut rock is like a baby, freshly brought to life. After hundreds of thousands of years, the pieces of rock are liberated from their deep seclusion by being severed from the base of the parent mountain.

The programme notes that the grandeur of rocks gives humans a sense of their insignificance in the grander scheme of things. Perhaps it is from this that their spiritual power emanates. As in Zen, the effect induces a diminishing of the ego in face of the sheer immensity and longevity of the rocks. And in the end all we are left with is ‘Gratitude’, as an ink-stone grinder puts it.

Rocks are thus shown to be a true object of worship, and it is to the larger rock on which we live that we owe our very existence. As the programme shows, rocks truly rock. We can only live in awe.

(For more of Green Shinto on the mystique of rocks, click here.)

*************

Christian Storms, climber, actor and tv producer

Christian Storms, the American featured in the NHK programme, writes:

‘Climbers like me tend to view history via geology, a primordial time before man. Each type of rock tells a different story about the history of the earth. Much like the people I have shared special moments with, rocks come in all kinds of forms, compositions and hardness: just like the characters I have met.

On this trip, I learned to appreciate rocks that I can’t climb, which was a first for me. I met Sugita-san, an old-school climber who has put up over 150 routes in the world-class limestone Bichu climbing area, which now has 400 routes. Climbing his first ascents was a real pleasure because he designed the routes. It felt like picking his brain or dating his ex-girlfriend.

Formed underwater in ancient coral reefs and from shells and skeletal fragments of living organisms, those limestone cliffs I climbed were once underwater, before Japan was ever Japan. I promised Sugita I’d return to develop some of my own routes – and I will.

There is nothing like a ferry ride, and Kitagi Island [out of Kasaoka port] is a real gem. Tsuruta-san was all smiles as he showed me an old quarry for limestone and marble, that s now filled with crystal clear water. Watching limestone being quarried using the old fashioned method was quite something. And the death-defying ladders I had to climb down were scarier than any mountain I’ve climbed.

Finally, finding an inkstone was special. But more than that, I got to make one, together with the master, Nakashima-san. To create something from rock, and to make something that has been used for over 700 years – it felt so primitive. Without this rock, there would have been no written world, no literature, no history.

As the musician Bob Dylan said, “How does it feel? To be without a home, like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone.” Okayama felt like home.’

***************

Places spotlighted in the NHK programme (see here):

Takahashi City in Okayama Prefecture is a popular destination for sports climbers. Rock climbing courses were first set up here in the late 1980s, and the area is now known by the name Bichu. TV producer Christian Storms is an avid sports climber. On this edition of Journeys in Japan, he scales one of the rock walls of Bichu. He visits an island that has a long history of producing high quality granite and inspects an existing quarry. He meets a traditional craftsman who uses the local slate to carve calligraphy inkstones by hand. And he discovers the profound connection that people here have long felt for their rocks.

Mt. Yoze-dake in Takahashi City is one of the most popular areas for sport climbing. The main climbing area, known as Bichu, is equipped with a parking lot, a rest house and a car camping ground.

Mt. Kinojo Visitor Center

On the summit of Mt. Kinojo you can visit the site of an ancient castle. The beautiful landscape is dotted with places associated with a legendary demon who is said to have ruled this area. Inside the precincts of Iwaya-ji Temple is an impressive rock formation that is believed to have been the demon’s residence. The Mt. Kinojo Visitor Center is 20 minutes by car or taxi from Soja Station on the JR Hakubi Line.

The most famous rocks in the world? The Zen garden at Ryoanji shows how Buddhism absorbed the native tradition of rock worship

A triad of sacred rock deities. This and the following pictures are from a remarkable collection of outstanding rocks by power spotter, Kara Yamaguchi (see https://www.greenshinto.com/2013/12/05/power-spotter/)