The Amami islands lie between Kyushu and Okinawa. Though technically they belong to Kagoshima Prefecture, they have more of the feel of Okinawa. There are five inhabited islands in the archipelago, of which Amami Oshima is the biggest. Total population is around 70,000.

The Amami islands lie between Kyushu and Okinawa. Though technically they belong to Kagoshima Prefecture, they have more of the feel of Okinawa. There are five inhabited islands in the archipelago, of which Amami Oshima is the biggest. Total population is around 70,000.

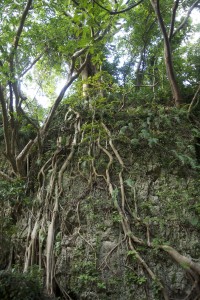

Offerings to a tree spirit. Simple, direct, genuine.

Together with Tokunoshima and Iriemoto in Okinawa, the islands are working towards World Heritage status for their subtropical evergreen broad-leaf forests, boasting endemic and endangered species. These came about because the islands were separated from Japan and the Asian mainland some two million years ago, and were warmed by the Kuroshio current coming from the south and bringing monsoon winds and relatively high amounts of rain. These special conditions led to unique life forms, giving rise to the expression ‘the Galapagos of the East’.

In previous postings Green Shinto has taken an interest in Okinawan religion because of the feeling that there is something older, more direct and more essential about the spirituality. There’s a sense of practices stretching back to ancient times, when creation myths tell of founding forefathers arriving from the south. As in the rest of Japan, ancestor worship is merged with animism, but unlike modern Shinto, female shamanism has managed to survive here, bucking the trend of a male priesthood and Meiji-style uniformity.

History

30,000 BC – Evidence of human habitation

1440-1609 – Ryukyu rule (under the sway of Okinawan kings). Hereditary noro priestesses.

1609-1871 – Satsuma rule; introduction of Zen by samurai ruling class in Kagoshima

after Meiji – incorporation into mainstream Japan

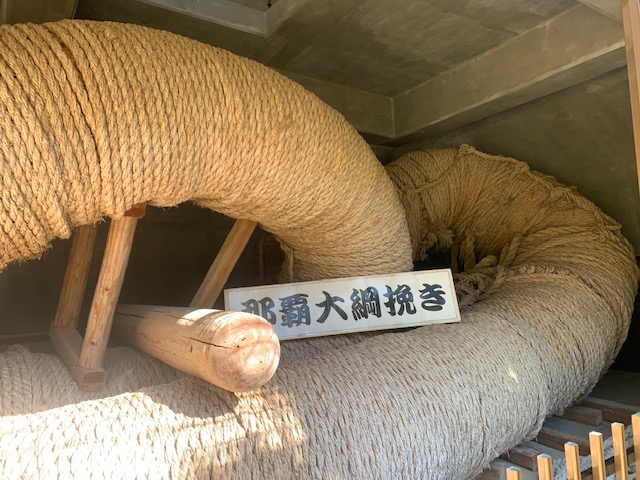

From 1440 Amami came under the sway of the Ryukyu Kingdom, and its religion took on the Okinawan style. This involved noro (female ceremonial priests), who were appointed by the state and were chosen from among the female dependents of administrative officials. In other words, they were the wives or daughters of representatives of the state, and the office was passed on to their descendants. The noro still exist, though shorn of any official status, and carry out six great ceremonies a year.

There’s a touch of Siberian shamanism about some of the matsuri in the islands.

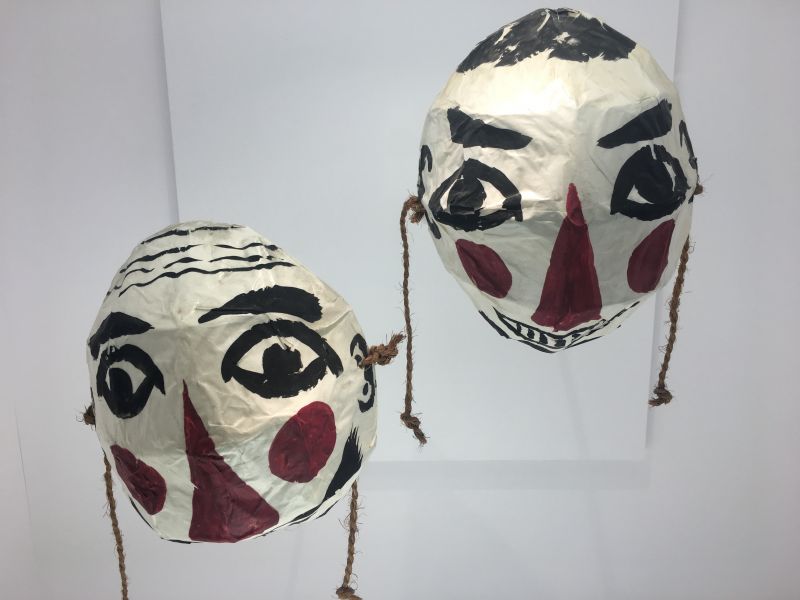

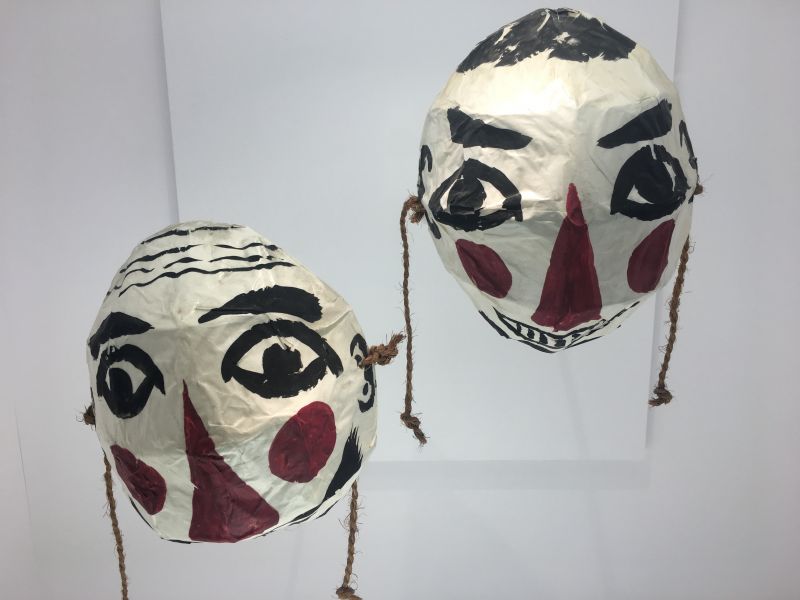

Along with the noro were shamanic females known as yuta. These women had a more personal role, offering psychic services such as divination and counselling. The idea was that being possessed, they spoke with the voice of the spirits. In other words, the yuta became the medium through which the will of the kami was transmitted, and masks worn in ceremonies signified the transformation. Interestingly, the yuta are addressed as kami, and the person to whom I was introduced was called Sakai-gami (please see Part Two).

Near the airport is the informative Amami Park, with hands on exhibitions about the islands (as well as a memorial museum for the astonishing artwork of Tanaka Isson). Watching the video of the various matsuri, I couldn’t help but be struck by the similarities to Siberian shamanism. Insistent drumming; grotesque masks; frenetic circling by participants. Mindful of the physiognomy, one can’t help feeling that it was here that northern style shamanism must have merged with currents from the south.

Shrines and temples

Drive around the island and you will be struck by the sorry state of the shrines on the one hand, and the relative absence of Buddhist temples on the other. The latter has a simple explanation. Following the Meiji Restoration, Shinto was declared the official religion and an anti-Buddhist campaign launched, known as haibutsu kishaku (abolish Buddhism and destroy the Buddha). Wikipedia states that between 1872 and 1874 eighteen thousand temples were eradicated, and maybe as many again from 1868 to 1872.

A noro has red points applied to her cheeks, a means perhaps of keeping evil spirits at bay

From what I could learn, Shinto is not much practised, and the only shrine with priests is Takachiho Jinja in Naze City. This helps explain why other shrines are so neglected, and I had the feeling that having been introduced in Satsuma times, the religion had not taken root. Locals I talked to said that though each area or community had a shrine, they were only used once a year for the annual festival. This was held under the auspices of the village elder.

As in Okinawa, one had the feeling that ancestor worship remained the rockbed on which the island spirituality was based. Villagers apparently visit family graves every month on the 15th. Though modern cemeteries contain standard Buddhist graves, in the past the practice was to leave bodies to rot in places already strewn with family bones. You can hardly get closer to your ancestors than that.

Asked about religious practice these days, I was told that new religions such as Soka Gakkai and Tenri-kyo had made inroads as had Catholicism. Underlying them though were the old ways, and there were places on the island known since ancient times as sacred. There were spiritual ‘wise women’ too. And so it was that I gained the telephone number of Sakai-gami, a yuta with a high reputation in the north of the island. Part Two tells of our encounter.

*************

For a report on Miyako Island, see here. For the first of five pieces about Okinawa, see here.

Amami folksingers, grandmother and granddaughter, who proved useful informants about the island religions

A puzzling monument, described in a pamphlet as marking the merger of the island myth with Tenson Korin (Shinto myth). No explanation as to why or when. The sign itself simply says, “Ayamaru Misaki, one of ten Amami beauty spots’.

The sorry looking entrance to the Haiden of Itsukushima Shrine, typical of the state of shrines generally.

Amami Oshima’s main shrine – Takachiho Jinja. The office was closed and there was no priest to be seen.

Offerings to an invisible life force.

Masks worn in one of the island matsuri. Spirit possession?

A guest house with a sense of humour. Ama terrace – Amaterasu.

The sacred hill of Ogamiyama, from which yuta draw water for purification. Was it the shape that made the hill special, or was it the view over the sea from which forefathers came?

A local villager explains about the sacred water emanating from Ogamiyama, used still today for purification by yuta before their rituals.

The Amami islands lie between Kyushu and Okinawa. Though technically they belong to Kagoshima Prefecture, they have more of the feel of Okinawa. There are five inhabited islands in the archipelago, of which Amami Oshima is the biggest. Total population is around 70,000.

The Amami islands lie between Kyushu and Okinawa. Though technically they belong to Kagoshima Prefecture, they have more of the feel of Okinawa. There are five inhabited islands in the archipelago, of which Amami Oshima is the biggest. Total population is around 70,000.