Those of us who live in Kyoto are aware of two vital clans in the river basin’s early history – the Hata and the Kamo. They played a decisive role in the religious development of the area, and their legacy remains evident nearly 2000 years later.

Though there were other clans, the Hata and Kamo achieved preeminence and the shrines they founded are amongst the city’s best-known. The Hata are associated with Matsuoo Taisha and Fushimi Inari, the Kamo with the Kamigamo and Shimogamo Shrines. At some point the two clans appear to have intermarried and formed an alliance.

It was with interest therefore that I came across an article about the early developments in Kyoto entitled ‘Activity of the Aya and Hata in the Domain of the Sacred’, by Bruno Lewin (tr. Richard Payne with Ellen Rozett, Pacific World, New Series, No. 10, 1994).

Sacred rock at Matsuoo Taisha in Kyoto, which recalls the rock worship of Korea and the immigrant origins of the Hata clan who founded the shrine

The article starts by pointing out that immigrants lay behind the introduction and dissemination of Buddhism in Japan. This was exemplified above all by the powerful Soga clan, who were opposed by conservative aristocrats backing vested interests in their tutelary kami. It even led to war between them.

Amongst the incoming waves of immigrants the most powerful were the Hata, who may have arrived in two waves before and after the turn of the fourth century. Their continental origins are unclear, and though they arrived in Japan from Korea it is thought they had previously entered the peninsula from China (there’s been much speculation about their Silk Road ties, leading to fanciful talk of middle eastern origins and Jewish or early Christian beliefs).

It is possible the Hata moved through Tsushima into Kyushu, then along the Inland Sea to a landing area in the Kobe/Osaka vicinity, before settling in Yamashiro (present-day Kyoto). There these Buddhist-inclined immigrants were to have a surprisingly strong influence on the native kami tradition, as we see in the extract below. The evidence suggests close connections of the ‘unique’ Japanese faith with its continental cousins.

***********************************

(Extracted from ‘Activity of the Aya and Hata in the Domain of the Sacred’

From amongst the old kikajin, the Hata acquired a special position in the domain of the sacred. It is remarkable that the Hata found entrance into the national kami cult, that they established Shinto shrines and were active as Shinto priests.

It is hardly probable that the Hata took on foreign religious forms, but rather that the Japanese cult of ancestors and nature deities may have corresponded with their own ancient religious form, which along with their ancient conceptions of the sacred had been influenced by many centuries of living with the Korean peoples.

Osake Jinja in Kyoto may once have represented the Hata family shrine where its ancestral founder Hata no Kimi Sake was worshipped

In contrast to the other old kikajin, the Hata possessed larger ancestral shrines, which were probably located at all of their places of settlement. The Osake shrines in Yamashiro (Kadono district) and Harima (Akaho district) are well known, which were consecrated to the memory of Hata no Kimi Sake. Also, a few Hata shrines should be noted which are mentioned in the Engi Shiki, but which no longer exist.

All of the kikajin (immigrants) have a close connection with the introduction and dissemination of Buddhism in Japan. In the same way that Buddhism was brought to Japan via China and Korea, they came into the country, and there are numerous monks to be found among the Korean and Chinese immigrants who had made Japan their adopted country since the sixth century. But also, the oldest strata of immigrants, who had already been residing in Japan for a century and a half prior to the introduction of Buddhism, show a certain affinity to the new teaching.

It is well known that beginning in the second half of the sixth century the powerful Soga clan brought their influence to bear in support of Buddhism, against the opposition of the conservative, high aristocracy. In close contact with the Soga stood the Kura families of the Aya and Hata, who-under the supervision of the Soga were to administer state finances. This may have contributed to the oldest foreign aristocrats, who, being under the influence of the Soga, accepted the Buddhist teachings early on.

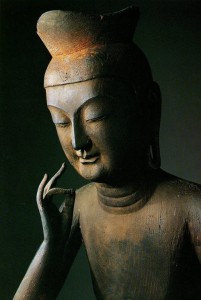

Hata no Kawakatsu, close advisor to Shotoku Taishi

The proof is found in some temple foundations which go back to the activity of the Kochi-no-Aya no Obito, the descendants of Wani, and of the Hata no Miyatsuko, the descendants of Yuzuki. [They founded] the Koryuji in Yamashiro. According to the Nihongi this temple was established in the year 603.’ In the Suiko-ki it is reported:

“The crown prince (Shotoku-taishi) spoke to all the dignitaries: “I have a statue of the Buddha who is worthy of worship. Who would like to receive this statue and devotedly venerate it?” – Then Hata no Miyatsuko Kawakatsu stepped forward and said: “I would like to venerate it.” Thus he received the Buddha statue and constructed the Hachiokadera for it.”

Hachiokadera is the original name of this temple, named for the settlement beside Uzumasa, the site of the main family. It was henceforth the house temple of the Hata, therefore it was also known as the Hata-no-kimi-dera. It is the oldest Buddhist temple in the district of today’s Kyoto.

In the year 818 the temple burned down for the first time. In the reports transmitted by the Nihon-kiryaku it is called Uzumasa-no-Kimi-dera, a sign that its ties with the name of the Hata lasted after its founding in Heian-kyo. Besides, on the temple grounds there is an Uzumasaden, in which Hata no Kawakatsu is venerated as the temple’s founder.

*******************

For earlier articles on the Hata, see Part One (Overview), or Part Two on Hata Kawakatsu, or Part Three on the Silkworm Shrine (Kaiko no Yashiro), or Part Four on the Triangular Torii.

Koryu-ji, once known as Hata-dera, is Kyoto’s earliest Buddhist temple and was founded by the powerful Hata clan

For earlier parts in this series on the Hata clan, please check out the following links:

Part 1: an overview of the Hata clan

Part 2: Hata no Kawakatsu

Part 3 on the silkworn shrine

Part 4 on the triangular torii