This is part of an ongoing series about travelling the length of Japan by train, and consists of passages with a Shinto or spiritual flavour. They are extracted from a longer book version due to be published by Stone Bridge in January 2024.

********************

For those so inclined, Japanese mythology is fascinating. The stories are the stuff of fantasy, yet the myths continue to sustain the ruling class by fostering mystique about heavenly origins. Emperor Hirohito may have renounced divinity at the end of WW2, but the coronation of the present emperor included a rite symbolising descent from the sun goddess (Amaterasu). The country’s premier shrine, Ise Jingu, still honours her as ancestor of the imperial family.

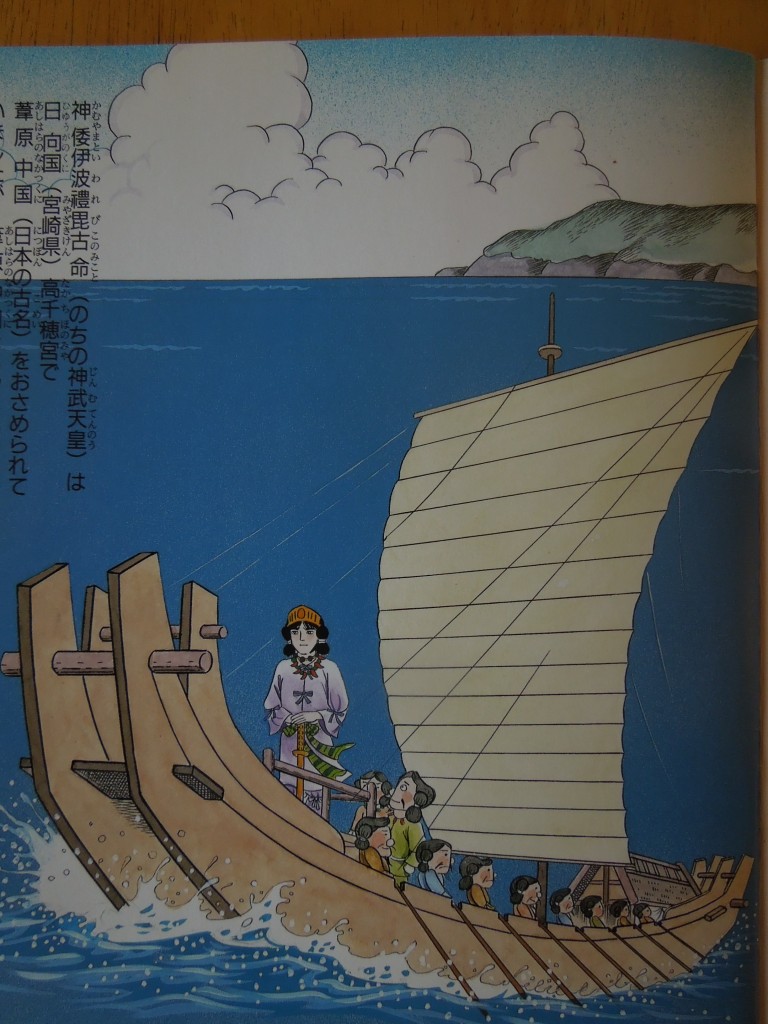

The myth of heavenly descent is known as Tenson Korin. It tells of how the sun goddess instructed her grandson to descend to earth, and how he touched down on a mountain peak called Mt Takachiho in southern Kyushu. This has long puzzled me. It is generally assumed that the early rulers of Japan, the Yamato clan, emigrated from the Korean peninsula. If that is the case, then surely they would ‘descend’ onto a mountain in northern Kyushu. Why should Mt Takachiho be singled out for this momentous event?

Faced with this puzzle, I concocted my own theory. It was sparked by the arrival of the first Europeans to Japan, for three Portuguese traders were caught in a storm while travelling along the coast of China, and their badly damaged ship was swept along by the Kuroshio Current to the Japanese island of Tanegashima. The same current flows towards Kinko Bay, in which Kagoshima is situated, and at the end of the bay Mt Takachiho is visible.

Because of the current, there are many links between coastal China and southern Kyushu. Japan’s earliest rice cultivation, imported from China, is found here, and archeologists have unearthed skeletons from around this time resembling those of Jiangsu Province. In addition, early myths about Amaterasu and silk weaving are similar to those of the Yangtze River delta.

At this point enter Xu Fu, a Chinese alchemist. According to accounts, he was sent by China’s first emperor in search of an elixir for immortality. The first mission ended in failure, following which around 210 BC he was granted sixty large boats, together with soldiers, crew and 3000 boys and girls equipped with various skills, This time he never returned, and in later years it was assumed that he had reached Japan. How intriguing, I thought. Could the Kuroshio Current have taken Xu Fu’s armada to the foot of Mt Takachiho? Could he be the inspiration for the heavenly descent?

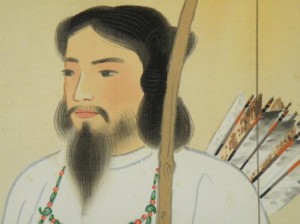

Not far from Mt Takachiho lies the town of Miyazaki and access to the Inland Sea. This prompts thought of the route of conquest taken by the Yamato clan, who migrated from Kyushu to the Nara basin. The mythology related in Japan’s earliest written works tell how Emperor Jimmu, Japan’s legendary first emperor, led the expedition.

Now here is a very odd ‘coincidence’. If you travel to the small town of Shingu on the Kii Peninsula, there are sites associated with the arrivals by sea of both Jimmu and Xu Fu. Just south of the town is a beach where Emperor Jimmu supposedly landed. And in the town itself is a creek where Xu Fu is said to have arrived. In Japanese Xu Fu is known as Jofuku, and in Jofuku Park is a grave where the Chinese alchemist is allegedly buried.

The legends of Xu Fu and Jimmu both date from early Yayoi times, when Japan underwent great cultural change. Could it be in fact that the two legendary figures were modelled on the same person? It would mean that Japan’s imperial ancestors came from China in search of immortality, landed beneath Mt Takachiho, made their way across the Inland Sea to Shingu, then proceeded overland to Yamato in the Nara Basin.

The more I thought about my idea, the more convincing it seemed. But when I tried it out on specialists in mythology, I found little support. Alas and alack, there Is nothing new under the sun, and I discovered one day that a Japanese professor by the name of Ino Okifu had come up with the very same theory. Wikipedia claims the idea has been discredited, though it offers no explanation why, and as far as I am concerned the theory remains a tantalising possibility. To the world at large Kagoshima may be a volcanic city where the Last Samurai died, but to me it is a gateway to the mythological past.

********************

For more on the same subject, see postings for the China connection (Parts 1-3) by starting here.