Just to the north of Kyoto, Ohara is a picturesque village with a traditional, rural feel. It’s known locally for its vegetables, but has a wider claim to fame as host to the celebrated Buddhist temple of Sanzen-in. The village has other temples of note, including Jakko-in which housed the tragic figure of Kenreimonin, mother of Emperor Antoku, until her death in 1214.

Along with its temples, Ohara has some interesting shrines which show how the religion is interwoven into the fabric of the village community and how it plays a vital part in keeping alive local folklore.

Ohara’s main shrine, Ebumi Jinja, stands on a mountain and is passed by the Kyoto Trail that runs round three quarters of the city. Easier to access is a branch shrine called Umenomiya, which stands beside the main road. It is unattractive as shrines go, and the surrounds look desolate. This is hardly representative of ‘a nature religion’ that one might expect in such a rural location.

The dominant building here, seen in the picture above, is a storehouse for the mikoshi, which is paraded round the village on May 5 each year. Unusually, the storehouse overshadows the shrine itself. Thee was a desolate air to the scene, as if the shrine had been cut off from its natural surrounds, though it continues to play a vital part in the community life.

As an auxiliary of Ebumi Shrine, Umenomiya enshrines Konohana Sukuyahime, goddess of Mount Fuji and the blossom-princess who represents life’s fragility. It is also understood to enshrine the empress and princess of Ebumi Shrine, known together as Himemiya. The kami thus have a strong female presence, though that is not at all evident.

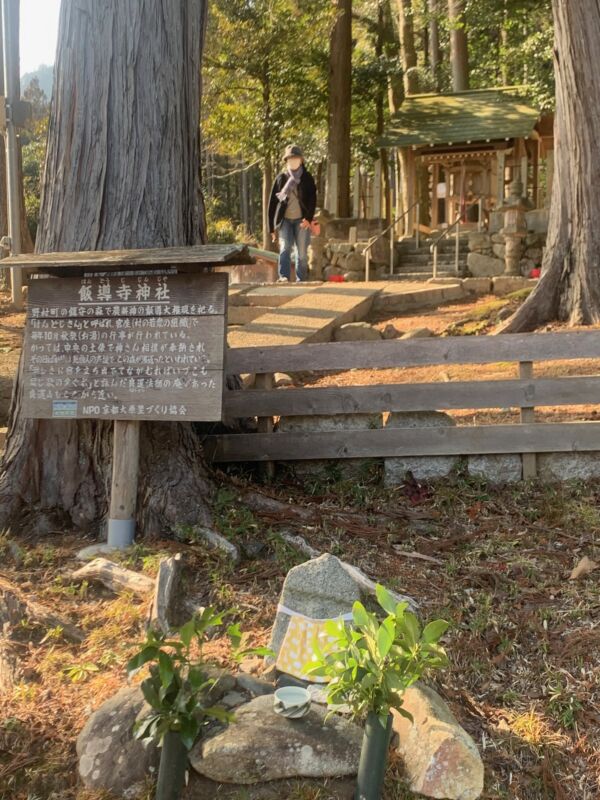

On the other side of the village stands a shrine with a highly unusual name in these post-Meiji times. It’s called Hando-ji Jinja, literally Hando Buddhist Temple Shrine. Before the Meiji Restoration, such syncretic titles were common, and very few shrines acted independently of their Buddhist neighbours. In fact one statistic I’ve seen suggests that only 10% counted themselves as purely Shinto with a dedicated Shinto priest, rather than being served by Buddhist ritualists.

Meiji fanatics were keen to strip Shinto of all Buddhist connections, so how did little Hando-ji Jinja survive? Well, according to the notice board it’s a Shugendo shrine, and the kami worshipped here is Hando Daigongen (an avatar, or Buddhist deity manifest in kami form).

On October 10 each year a miko performs a hot water splashing ceremony, and until recently on the same day there used to be a sumo competition for the enjoyment of the kami, with boys in the afternoon and adults in the evening. It started around 1942 during WW2 when there was a nationalistic sumo boom, and a dohyo was made. Such was the excitement that they even had a yokozuna come visit. As the boom passed in the postwar period, the practice fell out of favour and is no longer held.

A third village item to catch our attention was a piece of folklore sanctified by a small Shinto shrine, known as a hokora. A notice board told of a young woman called Otsuu who caught the eye of an aristocrat visiting Ohara one day. Captivated by her beauty, he took off to his palace back in Kyoto. But when she fell ill, he grew tired of her and returned her to Ohara. She was so distraught at this that she drowned herself in the river.

As her spirit left her body, it turned into a big serpent that haunted the village and scared the villagers. When the nobleman made another visit to Ohara, the serpent rose up and attacked him, but in the nobleman’s procession were armed guards who leapt to his defense and cut the serpent into three separate pieces – head, body and tail. That night there was a storm, during which a scream could be heard, and the villagers supposed this must be Otsuu’s ‘hungry ghost’ thwarted of revenge, so they took the serpent’s remains and buried them in three different places, performing rituals to pacify her soul. The place in the picture above, called Otsuu no mori, was where the head was buried.

So what can we learn from all this? The shrines of Ohara suggest Shinto is not simply ‘a nature religion’ but a mainstay of the community. It cherishes the past and fosters ancient customs. It represents continuity when all around is change. It exemplifies too how particularism can ally itself to a universal religion like Buddhism. It is, in the end, what gives a place like Ohara its identity.

Umenomiya was once a high-ranking shrine with strong imperial connections. It boasts a large wooded pond area adjacent to the compound, where seasonal flora are on display throughout the first half of the year. At the moment it’s full of iris, azalea and hydrangea. Simply stunning!

Umenomiya was once a high-ranking shrine with strong imperial connections. It boasts a large wooded pond area adjacent to the compound, where seasonal flora are on display throughout the first half of the year. At the moment it’s full of iris, azalea and hydrangea. Simply stunning! According to tradition, Konohana no Sakuyahime gave birth to a god on the day following her marriage to Ninigi no mikoto (ancestor of the imperial line). The speed with which she bore the baby led to her being patronised as a goddess of easy childbirth, as a result of which pregnant women come to pray for a safe delivery. The association with childbirth is furthered by a stone to the right of the Honden known as Matage ishi (Matage rock), for it’s said that the Empress Danrin who had been childless was able to conceive after stepping over it. She took some of the white sand in which the rock stands and spread it under her bed, which supposedly eased her in giving birth.

According to tradition, Konohana no Sakuyahime gave birth to a god on the day following her marriage to Ninigi no mikoto (ancestor of the imperial line). The speed with which she bore the baby led to her being patronised as a goddess of easy childbirth, as a result of which pregnant women come to pray for a safe delivery. The association with childbirth is furthered by a stone to the right of the Honden known as Matage ishi (Matage rock), for it’s said that the Empress Danrin who had been childless was able to conceive after stepping over it. She took some of the white sand in which the rock stands and spread it under her bed, which supposedly eased her in giving birth. Since the word for ‘giving birth’ is similar to plum (ume), there are about 500 plum trees at the shrine and pickled plums are on sale at the office. When the eighteenth-century Shinto scholar Motoori Norinaga donated a plum tree, he penned a short verse to go with it…

Since the word for ‘giving birth’ is similar to plum (ume), there are about 500 plum trees at the shrine and pickled plums are on sale at the office. When the eighteenth-century Shinto scholar Motoori Norinaga donated a plum tree, he penned a short verse to go with it…