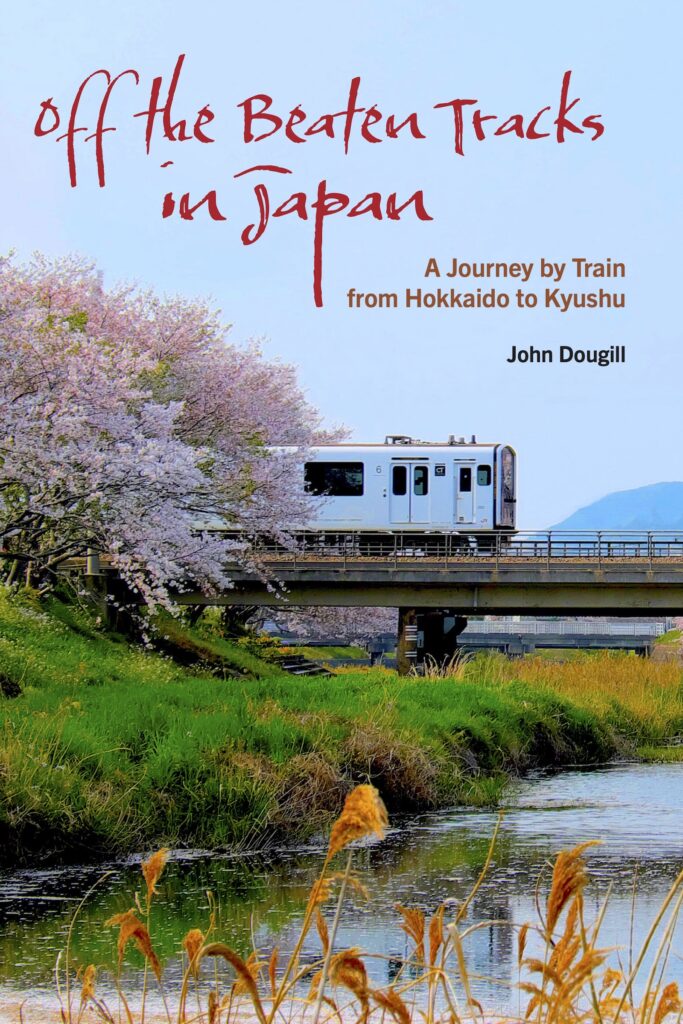

This is the concluding excerpt from a book to be published by Stone Bridge in Novemer 2023 entitled Off the Beaten Tracks in Japan. It concerns the kamikaze museum at Chiran, on the way between the most southerly manned station at Ibusuki and the most southerly unmanned station at Nishi-Oyama. As well as kamikaze, Chiran is notable for its collection of well-preserved samurai houses and gardens.

************

A short taxi ride away from Chiran’s samurai houses lies the Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots. Why is it located in such an out of the way place, one may well wonder? The answer is simple: the site was once a wartime training school for pilots, which in the later stages of the war served as a base for kamikaze missions. The museum is generously funded, and the spacious rooms are able to house a collection of planes, with pride of place going to the Mitsubishi Zero fighter favoured by the kamikaze.

The exhibits are all in Japanese, save for one major exception; the translation of a touching farewell letter written by a teenage pilot to his mother. Despite its name, however, the Peace Museum seemed more like a celebration of self-sacrifice. Never again was the message at Nagasaki. I did not get that feeling here.

The ethos of samurai and kamikaze is rooted in the suppression of self, and the cultural values which stem from that are what make Japan so comfortable a place to live. Donald Richie wrote of the paradox this presents to foreign residents like himself, for the very qualities they find praiseworthy derive from darker elements in a feudalistic past – conformity, repression, obligations. It is a great irony that the Vietnam War draft dodgers who headed for Kyoto in search of liberation took up Zen and found themselves undergoing a taming of the ego similar to that implemented by drill sergeants in the US military.

Outside the museum are the inevitable cherry trees, for the truncated lives of kamikaze youth are seen poetically in terms of falling blossom. There is too a reconstructed barracks where the young men spent their final days. The most poignant element is a sparse wooden dormitory with beds set close to one another. The neatly folded bedding is set out in a row, Zen-like in its precision.

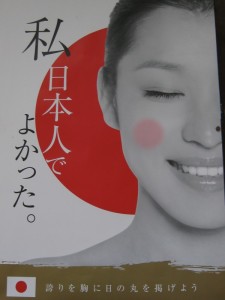

Cherry blossom – kamikaze – samurai – Zen. At journey’s end I was being presented with a stereotype, but it is an image that Japanese themselves have been keen to promote. It is one that sustains the status quo and makes Japan a deeply conservative country. For all the fervid Westernisation of the past 150 years, the inner core of Japaneseness remains intact. The words of Lafcadio Hearn, written over a hundred years ago, still contain a large measure of truth. ‘The nation has moved unitedly in the direction of great ends,’ he wrote, ’submitting the whole volume of its millions to be moulded by the ideas of its rulers.’ And the engine driving this unified force was what Hearn described as ‘the absence of egotistical individualism’. He credited this to the moral power of Shinto on the one hand, and on the other to the mastery of self promoted by Buddhism.

There are many individuals who exemplify the close ties between Zen and Shinto in Japanese history, particularly in the period before an artificial line was drawn between Buddhism and ‘the indigenous religion’ in Meiji times.

There are many individuals who exemplify the close ties between Zen and Shinto in Japanese history, particularly in the period before an artificial line was drawn between Buddhism and ‘the indigenous religion’ in Meiji times.

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?

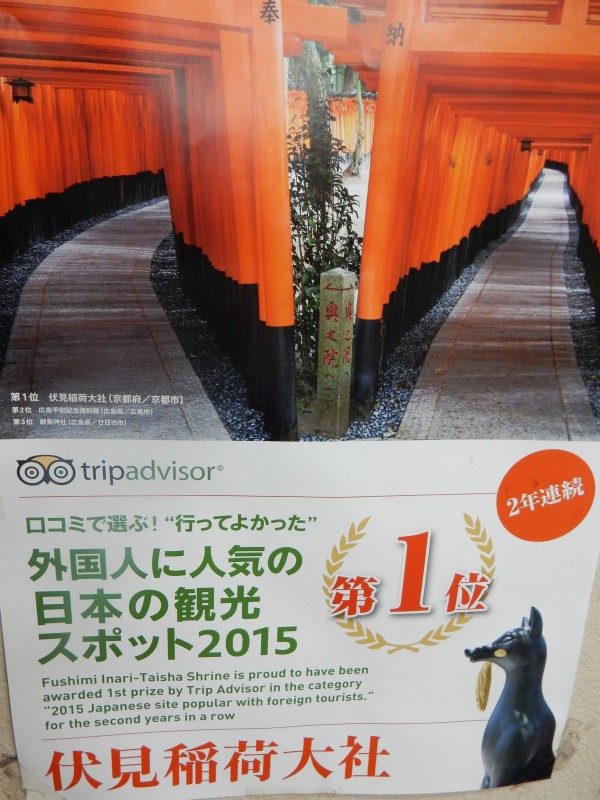

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

In this respect one has to wonder if Zen is not a more sophisticated view of the notion that humans are the children of kami. In other words, we all have ‘kami nature’ which is pure in spirit, just as in Zen we all have buddha-nature. It’s why we need the ‘magic cleansing’ of the oharai from time to time, to clean us of the dust of this world. No wonder that both Shinto and Buddhism use mirrors on their altars.

In this respect one has to wonder if Zen is not a more sophisticated view of the notion that humans are the children of kami. In other words, we all have ‘kami nature’ which is pure in spirit, just as in Zen we all have buddha-nature. It’s why we need the ‘magic cleansing’ of the oharai from time to time, to clean us of the dust of this world. No wonder that both Shinto and Buddhism use mirrors on their altars.