This is part of an ongoing series about the Shinto way of death, adapted with permission from an academic article by Elizabeth Kenney. It shows how traditional Shinto arrangements differ from those of the Buddhist funeral. Though the research was carried out in the 1990s and some of the information is dated, the fundamentals still apply. For the original article, see Elizabeth Kenney ‘Shinto mortuary rites in contemporary Japan.’

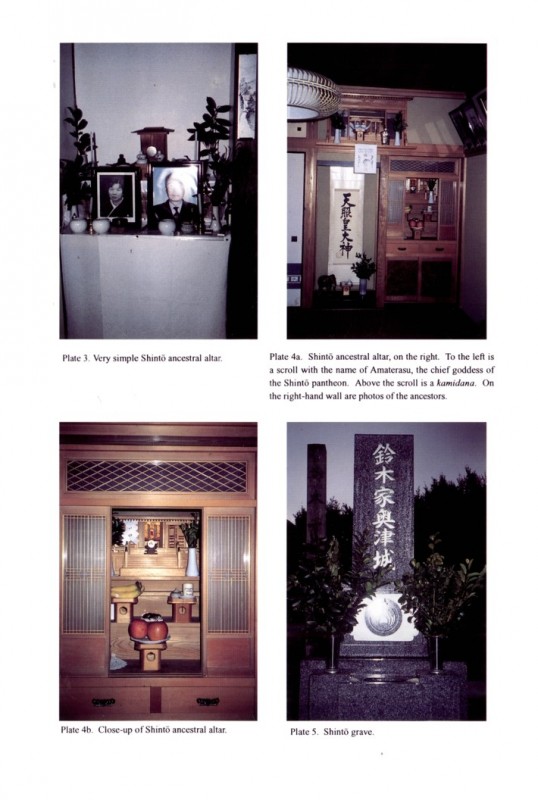

Illustrations of Shinto altars and grave taken from Elizabeth Kenney’s original article

Shinto cemetery (thanks to Keith Adams)

The Shinto grave and afterlife

Shinto shrines do not contain cemeteries and, in general, Shinto families do not use Buddhist temple graveyards. Therefore, most Shinto graves are located in public cemeteries or on private land (even in a family’s own backyard).

Typical Buddhist-style grave (for the poet Fujiwara no Teika)

Naturally, tombstone styles that seems “too Buddhist” are avoided (for example, the old-fashioned pagoda-style tombstone. It goes without saying that a Shinto tombstone will bear no Sanskrit letters and no Buddhist phrases (such as namu amida butsu or namu myô hô rengekyô). A modern Shinto tombstone is typically an obelisk. A similar rectangular structure is standard for new Buddhist graves, but with no taper toward the top. The difference is precisely that: difference, a subtle variation that signifies Shinto identity. There is nothing inherently Shintô-esque about the obelisk.

A Japanese tombstone typically has the words “the grave of X family” engraved on the front. In the case of a Shinto grave, the word haka is avoided — apparently, a taboo Buddhist word — and the term okutsuki is substituted.

As we have seen, incense is marked as Buddhist, so the Shinto grave does not have a stand for offering incense. Instead, there is sometimes a stone table in the same shape as the wooden table used for Shinto offerings during funerals. The Shinto grave may be encircled by a tama-gaki picket fence, a style of fence often seen at Shinto shrines.

Peering into the afterworld: according to folklore, this boulder in Shimane Prefecture separates our world from that of Yomi, or the dead

The afterlife

Shinto funerals now have a codified form, but there is no corresponding codification of the Shinto conception of what happens to the deceased. The Shinto establishment discusses the afterlife only in terms of the mythology, providing historical and scholarly perspective but not prescribing any eschatological views for its followers. Thus, notions of the afterlife remain diverse and more suited to anthropological than doctrinal investigation.

As we have seen in the funeral, the Shinto dead become guardian kami of their household. This is a postmortem position granted to all the dead, regardless of their virtue or status in life. Beyond that, people are free to envision the afterlife in whatever terms and to whatever extent they wish. Most Shintôists, whether priest or lay, have only modest interest in the question of what happens after death.

One Shinto priest had this to say: “After death, the spirit becomes a bird and goes to the top of the house. Then it flies to a nearby tree and stays there for fifty days. After that, the bird-spirit goes to the land of the dead.” This is an unusually definite delineation of the postmortem destiny. It is clearly indebted to mythological themes.

For the most part, Shinto followers have no such definite visions and do not feel a need for them. The funeral ritual is important for a variety of other reasons: because it honors the dead, because it serves as a crucial expression of the family’s non- Buddhist identity or anti-Buddhist sentiments, but not because it is a key to the Shinto afterlife.

Leave a Reply